Over the past week, we've all been hearing a lot about…

A digital poltergeist?

On the evening of October 31st my wife and I were relaxing on the couch after having put all the kids down for bed. My feet were on the coffee table as I scrolled through the infinitely-scrollable but never-quite-good-enough list of Netflix selections, and Ashlee was catching up on emails on her phone. At some point, still looking at her phone, she asked, “Did you sign us up for an Audible subscription?” [Cue thunder and chilling organ music.]

As a technologist with a pretty good idea of the types of schemes ne’er-do-wells often employ, my initial knee-jerk response was, “Don’t click any links in the email! It might be a phishing attempt.” She showed me the email in question, and my suspicions were replaced with incredulity and mild amusement.

“Your first title is waiting in your Library, found in the app,” the email read. What was that first title, you ask? Something very spooky indeed: There Was an Old Lady Who Swallowed a Bat by Lucille Colandro. I recognized the title and cover art. It was, in fact, a book we had checked out from the library and read to our two boys in the weeks leading up to Halloween.

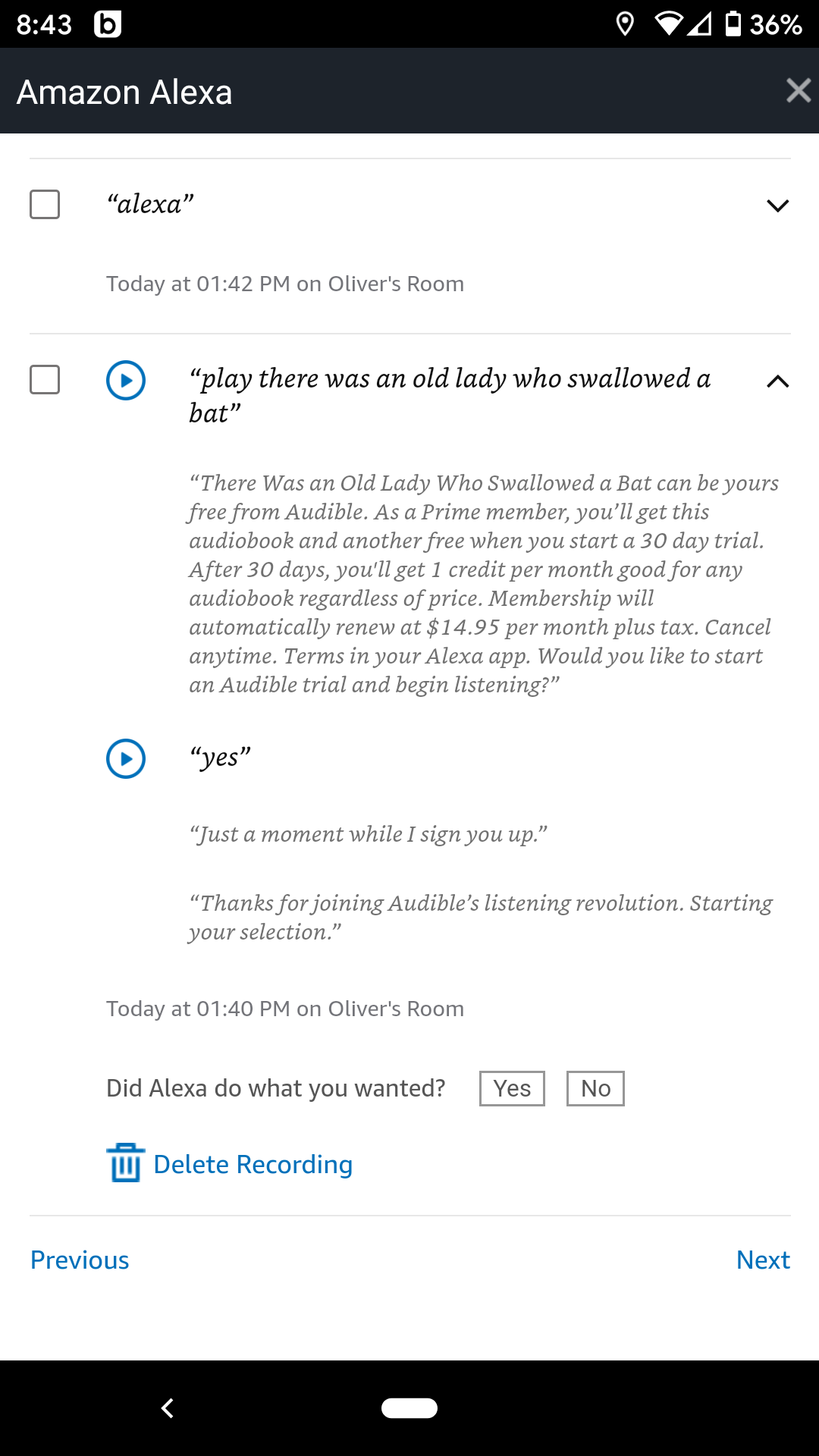

At that point, I had a pretty good idea of what had happened. Pulling out my phone, I opened the Alexa app and navigated to the Voice History section (Settings → Account Settings → History). If you own/use an Alexa-enabled device and have never checked this out, you need to. Some people find it alarming to look at (look at all this data they’re collecting, oh my!) — I find it informative. At least there’s some degree of transparency there, right? In the voice history, you can actually review a log of everything you’ve ever said to Alexa, including the recording of your voice at the time the command was given and Alexa’s subsequent response.

Scrolling through the voice history, I quickly found what I was looking for. It was during Oliver’s rest time, when he was sitting in his room looking through picture books and listening to music, that he said to Alexa, “play there was an old lady who swallowed a bat.” My guess is that, given we’ve sang the book to him before, he was just trying to play a song on Amazon Music.

Alexa, despite having parsed the recorded audio into text correctly, had incorrectly guessed his intention. Her response:

“There Was an Old Lady Who Swallowed a Bat can be yours free from Audible. As a prime member, you’ll get this audiobook and another free when you start a 30 day trial. After 30 days, you’ll get 1 credit per month good for any audiobook regardless of price. Membership will automatically renew at $14.95 per month plus tax. Cancel anytime. Terms in your Alexa app. Would you like to start an Audible trial and begin listening?”

At this point, Oliver, being a four-year-old, would have had no idea what was just explained to him. I imagine it sounded something like the adults in Charlie Brown: “There Was an Old Lady Who Swallowed a Bat can be yours [wah wah WAH-wah-wah…] Would you like to [wah wah-wah wah…] and begin listening?” Yep, he sure would! So, of course, he said yes.

One of the laughable points of this story is that, when you expand any of the voice history items, you will see the question, “Did Alexa do what you wanted?” The user is invited to respond “Yes” or “No.” The laughable part is that when you click “No,” the message changes to, “Thank you! Your feedback helps Alexa understand you better.” I don’t think I expected anything more than that type of response, but it’s still not super helpful to my present situation. What about canceling the unintentional subscription? Imagine ordering food at a fancy restaurant and the waiter brings you the wrong meal. He or she asks, “Is everything to your satisfaction?” and you reply, “No, this isn’t what I ordered. It’s not even close.” The waiter gives a warm smile and replies, “Thank you! Your feedback helps our chefs and waiting staff understand you better.” He then walks off, and you’re left to pick up your jaw from where it’s lying on the table.

Smart enough to make mistakes for us

I know, I know… it’s not a fair comparison, but it does illustrate an interesting point. Smart devices are “intelligent” enough to make decisions that have real-world consequences, but they’re rarely smart enough to fix things when they make a mistake. Voice-enabled devices, “smart homes,” and the like are letting us do increasingly more things through a voice interface. Specifically, these relatively insecure, marginally-intelligent decision-makers (e.g. Alexa, Google assistant, Siri, etc.) are capable of doing more and more things that were previously handled by more secure, competent (hopefully) decision-makers: ourselves. Things like signing up for subscription services, purchasing products with a credit card, calling the police, unlocking a door, etc.

Why do I say voice interfaces are relatively insecure and only marginally intelligent? Simply put, life is complicated. Machines can’t handle undefined situations (yet), whereas a human can. At the core, once you cut through all the machine learning and artificial intelligence layers, what you have at the end is programmed decision logic based on a probabilistic prediction. That is, given the data it’s presented with, your voice-enabled device makes many different decisions by feeding the data into trained machine learning models, predicting a best course of action from a list of predefined possible outcomes, and then executing that action.

For example, consider my four-year-old’s query from the machine’s point of view:

“Play there was an old lady who swallowed a bat.”

- Voice Analysis: Who is the speaker? Alexa may be able to tell distinct individuals apart, but it clearly wasn’t smart enough to recognize that 1) it was a young child, and 2) that child shouldn’t be allowed to make a purchasing decision. That’s a no-brainer for an adult, but it wasn’t something the machine was programmed to consider.

- Transcription: Given an audio recording, what words, phrases, or sentences were spoken? Alexa made an accurate transcription (though several other attempts by my son weren’t as successfully transcribed).

- Text Analysis: What are the grammatical structures, key phrases, topics, etc. being discussed in the given text? Alexa identified the phase “there was an old lady who swallowed a bat” as a piece of media. The imperative “play” was also identified as a user command.

- Intention Analysis: What is the user trying to do? Alexa incorrectly assumed the user wanted to listen to an audiobook, despite the user’s account not having an Audible account. If you’ve ever heard, “I can’t find any enabled video skills…” while trying to play music, you know that this kind of misunderstanding happens often enough. It also incorrectly assumed that the user wanted to be asked about signing up for Audible, which is something in Amazon’s best interest, but not necessarily in the user’s best interest…

Granted, this is a rough approximation of only a fraction of the systems and models involved in a single interaction. Artificial intelligence software today can do a really good job at these sorts of individual tasks — even chaining them together to produce meaningful results — but it’s still a very long way from achieving general intelligence, a term that roughly means “the ability to perform any task a human can.”

Surviving the jump scares and hoping for happy endings

With voice-enabled devices, smart devices, and AI in general, we are increasingly pushing secure decision-making power to machines that cannot think like us. They cannot think as broadly as we do — not every edge case can be programmed. They cannot think as compassionately as we do — machines lack emotional understanding. They cannot always act in our best interest — these are products are, after all, sold by companies whose goal is to make money. However, with the right combination of integrity, ingenuity, and accountability, I believe smart devices can have a positive impact on our lives. In fact, it already is.

AI has proven a force for good in many applications, including security (believe it or not). Unsupervised learning techniques help companies spot fraudulent activity on a scale much larger than humans would be able to handle. In healthcare, machine learning models process disparate patient information to help doctors diagnose diseases. The democratization of AI and machine learning is allowing researchers to better understand the ocean pollution problem. Scientists and conservationists use image processing algorithms to help track marine wildlife using submitted whale fluke (tail) photos. This small smattering of use cases represents only a fraction of the systems developed and being used for social good.

I have no doubt that smart devices will continue to steadily improve, and I’m willing to ride out the growing pains to see where the technology will go. More than that, I’m excited to be part of these formative years, working for a company that helps others effectively implement machine learning and AI solutions. Despite the concerns being raised by many about the dangers of such technology, I’m hopeful that we can, as a society, collectively shape it for a brighter future. Smart devices are still in their adolescence, so they can be expected to excite us one moment and disappoint us the next; to simplify some aspects of our lives while complicating others; to wrestle with the complexities of trading convenience for security. I’m looking forward to seeing where these technologies take us, despite the occasional “spooky” experience!

Update as of January 2020

I did a bit more research on an unanswered question—namely, whether you could turn off voice purchasing. Short answer, yes… but does it really protect your wallet the way it should?

There is a way to turn off the “Voice Purchasing” feature in the Amazon Alexa app settings, but I’m not convinced that it works. For one, I don’t know for sure if it prevents Alexa from subscribing to or upgrading things that can eventually cost money. For example, I was trying to play white noise on an echo (for which there is a free skill available), but for whatever reason the skill that it chose to surface at this particular moment was a “premium” white noise skill that had a subscription cost of $3 per month. I declined activating the skill, but again, had it been my four-year-old, would it have allowed him to purchase it?

Furthermore, turning off voice purchasing doesn’t prevent Amazon from their own nefarious marketing ploys to upgrade your account. It wasn’t until I went to cancel my new (unwanted) Audible account that I noticed we had been upgraded to Amazon Music’s family plan instead of the individual plan that we previously had (months ago!!!). I know that my wife and I did not upgrade our account. However, with an individual account, if you ever ask to play music when it’s already playing on a different device, Alexa will ask if you want to upgrade to a family music plan. All it would have taken was for our four-year-old to say “yes” to that simple question, and suddenly we’re paying more each month without meaning to.

Artificial intelligence at this level has a long way to go.

This Post Has 0 Comments